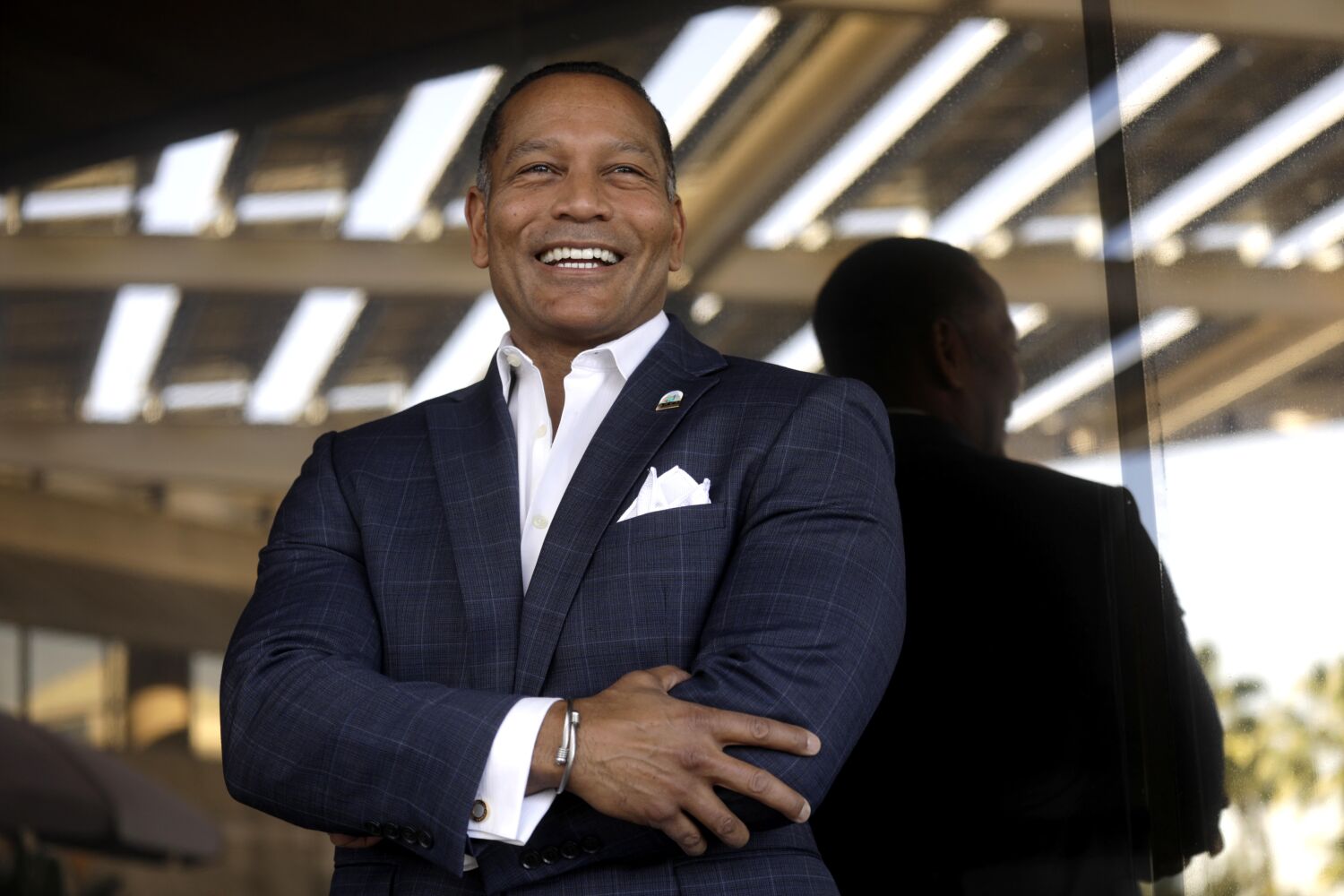

Rodney “Blair” Stewart listened attentively during a recent City Council meeting, jotting down notes as residents described their concerns — park modernization, traffic problems, city-sponsored events downtown.

Photographs of past mayors — all white men until 1982 — hung on the walls around Stewart, who last November was elected Brea’s first Black council member.

Only 1.2% of the city’s 47,500 residents are Black. Stewart fits right in with the Republican establishment, enjoys backing from influential insiders and is calling for strong relationships with small businesses and the Chamber of Commerce.

But for an Orange County city that was once a “sundown town” and that recently held heated debates about its Ku Klux Klan past, Stewart’s milestone is significant.

At some point during his four-year term, he could be appointed to the mayor’s seat by his colleagues, and his photo would join those of his predecessors in the council chambers.

“We’re moving toward an environment of inclusion,” said Gabriel Dima-Smith, 31, a Brea resident and political consultant who is Black. “This definitely is a symbol that can build confidence and inspire youth of color in the city that they can do great things here. How strong the symbol is depends on what he does on the dais.”

The Brea City Council has yet to catch up with the diversity of the upper-middle-class suburb it represents. Three of Stewart’s council colleagues are white and one is Latino, in a city that is 40% white, 30% Latino and 25% Asian American.

Stewart, 51, a firefighter in Torrance, downplayed his race during his campaign — “If I started talking about being the first Black city councilman in Brea, everything else that I’ve done in my life takes a back seat,” he said.

But his victory shows how far his hometown has come. He came in second, with 8,880 votes, in a contest where the top three captured a seat.

“I probably wouldn’t have won in the 1980s,” he said. “Fast forward to now, to get the second-most votes as a political newcomer — a Black newcomer — yeah, there’s something to be said about that.”

Brea’s demographics roughly mirror those of Orange County as a whole, which is 2.2% Black. Rhonda Bolton, a Democrat, became Huntington Beach’s first Black council member in 2021.

Racist taunting of students of color, particularly at sporting events, still happens with alarming regularity in Orange County. At a basketball game at Laguna Hills High last year, someone in the stands called a Black player a “monkey” and other insults.

The Stewart family moved to Brea in 1982, when Blair was 11. That same year, Norma Arias Hicks became the first woman and the first Latino to serve as mayor.

Stewart’s mother, an immigrant who was Japanese and Dutch, raised him and his two brothers on her own, working at local grocery stores.

Sometimes, Stewart’s shoes had holes in them, and classmates teased him, he recalled.

He was a standout basketball player at Brea Olinda High School, but some white parents didn’t want their daughters to date him, he said. A few times, strangers called him the N-word as he walked down the street.

“My mom always taught us that people are going to hate,” he said. “People are going to make racist remarks. You can let that define you or you can move on and focus on what your goals are.”

In Brea, Stewart also found mentors, especially among his high school coaches, including Chris Emeterio, now the assistant city manager. Anonymous donors left athletic shoes on his doorstep, knowing he couldn’t afford them.

“It was a good thing that my mother moved us here,” he said. “Brea has been very good to me and my family.”

After graduating from high school, Stewart joined the Marines, where he graduated boot camp as a top recruit and served for eight years.

Stewart came back to Brea in the late 1990s, studying criminal justice at Cal State Fullerton.

In 2000, he joined the Torrance Fire Department. There were a “handful” of other Black firefighters, Stewart said, but they have since retired or transferred, and he is now the only one.

Racial bullying has been a problem in some fire departments, but Stewart said he hasn’t had issues.

After living in Corona, Stewart returned to Brea again in 2018, while the city was in the midst of a racial reckoning.

A battle was underway over renaming Fanning Elementary. Education pioneer William E. Fanning’s name had surfaced on a list of O.C. Ku Klux Klan members from the 1920s.

School board meetings grew increasingly tense, and the Fanning family disputed the veracity of the Klan list. A study by the Brea Museum and Historical Society questioned Fanning’s Klan membership and stressed that there was no city ordinance codifying the “sundown” rules.

In early 2019, the school board voted to keep the Fanning name. But the following year, after the nationwide protests against George Floyd’s murder came to downtown Brea, the Fanning family asked the board to rename the school.

The Brea historical society has since joined the “Unvarnished” project, which published a history of the city, describing its origins as an oil town that adopted covenants prohibiting people of African, Chinese and Japanese descent from living there.

Sundown town practices “helped maintain Brea’s mostly white population,” the history said, citing a resident, Alice Thompson, who said in 1982 that there had once been no Black people in the town and that the Ku Klux Klan was widespread in the 1920s.

“An official ordinance was unnecessary as residents clearly understood that Black people were not welcome overnight,” the “Unvarnished” history said.

Stewart said he stayed out of the Fanning Elementary controversy. But he doesn’t gloss over the city’s past.

“If you have a ‘sundown town,’ you’re probably going to have members of the KKK in leadership positions,” Stewart said. “I’m always one of those people that says you should not forget history.”

Stewart remembers watching the movie “Back to the Future” as a boy. In one scene set in the 1950s, a diner owner scoffed, “A colored mayor? That’ll be the day.”

Stewart’s mother explained to him what a mayor’s job is and said, “You can be whatever you want to be, if you make the right decisions and work hard.”

The lesson stayed in the back of his mind, but he didn’t seriously consider running for office until recently, as he neared retirement as a firefighter.

Serving on the council comes with a stipend of about $680 a month but is essentially a volunteer position.

“I certainly want to be a good custodian of what Brea has already accomplished, whether it be fiscally or keeping Brea’s crime rate low,” he said. “I just want to be able to invest my time in Brea and serve the city that I love and that has given me so much opportunity.”

After taking the oath of office in December, Stewart addressed the audience and his fellow council members. He spoke about being raised in poverty by an immigrant single mother. He didn’t mention the racial milestone.

Brea Councilmember Steve Vargas, a Republican, supported Stewart’s candidacy. Voters wanted a fresh face on a council dominated by long-term incumbents, Vargas said.

“Our city has been incredibly diverse,” Vargas said. “We’ve got to make some positive changes in the future. We elected somebody that shows people want a change.”

Stewart won’t be the only Black official in Brea — the city attorney, the community development director and the city clerk are all Black.

“Is it a surprise my brother got elected? No,” said Stewart’s twin brother, Ed. “But my brother has to be relieved that we have come a long way. So has Brea.”